Book About Youth With Disabilities- Sooner is better for teens with disabilities entering the workforce

How old were you when you got your first job?

I’m sure it wasn’t when you were twenty or twenty-two or … never.

You likely got your first job when you were in your early teens. That’s what most of us did.

We babysat, delivered newspapers, scooped ice cream, pumped gas, washed cars, mowed lawns, shoveled snow, skimmed pools, raked leaves, walked dogs, sang Christmas carols door-to-door for TIP money, weeded gardens, sold lemonade, worked at flea markets or as lifeguards at community pools, retrieved our neighbor’s mail while they were on vacation, became junior camp counselors, caddied for golfers, or any number of other jobs when we were thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen-years-old. They may not have been the most glorious jobs, of course. But they earned us money, made us productive, and gave us self-worth.

If we were all working at jobs when we were those ages, then why shouldn’t youth with disabilities also be working at those ages, as well?

Well, I believe they should.

Truth be told, to help level the playing field in this highly competitive job market, I believe differently-abled youth should actually be getting a head start to work—not a late start or a no start. I espouse kids with disabilities learning about careers and being provided vocational training in schools when they are eleven and twelve and thirteen so that by the time they reach their middle teens they will at least have some work experiences including job samplings, volunteering, and even paid employment reflected on their resumes. (Ask most average kids between ages eleven and sixteen what a resume is. Prepare to receive a blank stare accompanied by an open mouth.)

I don’t want to speak disparagingly of the educational system, but this training is NOT being done for kids at those younger ages in traditional schools.

That’s most unfortunate.

It’s not the fault of the teachers—most special education teachers are dedicated angels who give their all for the betterment of their students. No argument there. They teach what they are instructed to within the programs and guidelines set forth by the administrators, both federal and state.

I believe it’s the restrictive policies and programs that are the problem and need to be rethought and reformed with fresh new ideas to better serve our children with challenges. I’m trying my best not to belabor the point, but as it is now, most traditional schools don’t even begin to engage their special education population into vocational programs until a student is sixteen-years-old.

And that’s waaaaayyyyyyy too late.

And whatever limited vocational opportunities arranged by traditional schools end once the student graduates. Kids often get lulled into thinking they have long-term jobs because their school arranged for them to clean tables or fold laundry or box goods one or two days a week during school hours. Then when the student graduates from high school and tries to continue the job they’ve been doing, the temporary host job site does not allow them to continue because they’re no longer part of the school program—they’ve already graduated.

Bye-bye.

When this happens, students and parents alike are left scratching their heads, wondering what happened and where time went. Then there’s the looming fear of what to do next. The images of graduated children sitting home all day with nothing to do are disconcerting, to say the least.

In stark contrast, if employment is secured in “real” jobs—defined as ones that have the potential to last beyond high school graduation—while students are still in school, there’s a good chance that most kids will maintain those jobs when they graduate.

I know. I’ve helped make it happen. For years. With countless youth—thanks to the forward-thinking nontraditional schools or proactive parents that privately hired me.

Kids wouldn’t have the daunting task of finding work on their own or with an agency employment counselor once post-high school adult life begins. They’d already be in a job of their choice for a few years. That experience will also help them in their future vocational endeavors.

And that’s a great thing!

Until school special education vocational programs are revamped to provide more individualized vocational services to students with disabilities—starting with early intervention for kids aged 12 and 13-years old—parents need to step in and provide pre-employment training to their children with disabilities, up to and including helping find their kids jobs when they are younger (13, 14, 15).

And if schools and parents won’t do it, then parents and schools should contract with outside companies to get it done. However it gets done, there must be early intervention for our children with challenges to succeed not only in the business world, but much more importantly, in life.

It’s a simple equation: Early intervention = success.

Don’t just take my word on it, take Dr. Temple Grandin’s word on it.

Temple Grandin is a college professor, world-renown animal behavior expert, best-selling author, lecturer, and formerly one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People. As perhaps the most famous person in the world with autism, Temple said she began her work experience when she was just thirteen-years-old, and advocates kids getting out to work sooner rather than later.

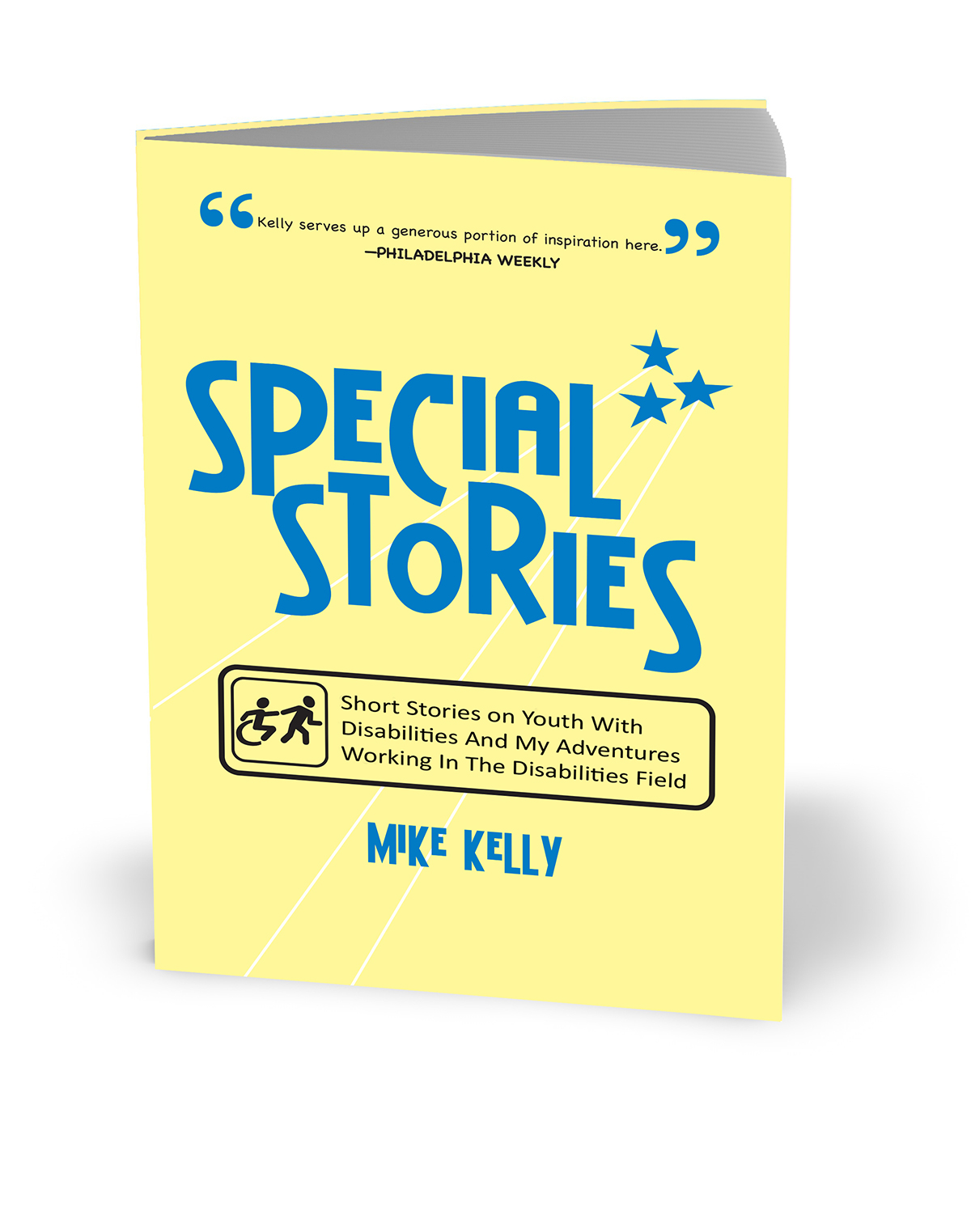

To read more stories like this and to learn about the new book, “Special Stories: Short Stories On Youth With Disabilities And My Adventures Working In The Disabilities Field” by Mike Kelly (2017, Vendue Books), visit www.specialstoriesbook.com.